The story of Drueding Brothers is a uniquely American tale of immigration, innovation, and industrial success—rooted in the values of hard work, faith, and care for community.

From Germany to Philadelphia

Charles and Henry Drueding were born in 1857 in Cloppenburg, Germany. At the age of 14, they immigrated to the United States and eventually graduated from the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy. In 1877, the brothers opened a pharmacy at the corner of Lawrence and Master Streets in Philadelphia.

(“C. C. Drueding Dies; Leather Executive,” 1939)

That unassuming corner would grow into a manufacturing empire and a cornerstone of industrial Kensington.

An Innovation That Changed an Industry

Originally, “chamois” leather came from the chamois, a goat-antelope species native to the Alps of Switzerland. Due to the scarcity and difficulty of hunting these animals, alternatives were sought, and sheepskin emerged as a practical substitute.

(E.B. Fortmann – Drueding Bros, 1924)

In 1885, Charles and Henry Drueding developed a process for tanning sheepskin into chamois leather—a breakthrough that would come to define their legacy. They began manufacturing chamois skins in the United States, operating under the name The Enterprise Chamois Works, which later became Drueding Brothers Company.

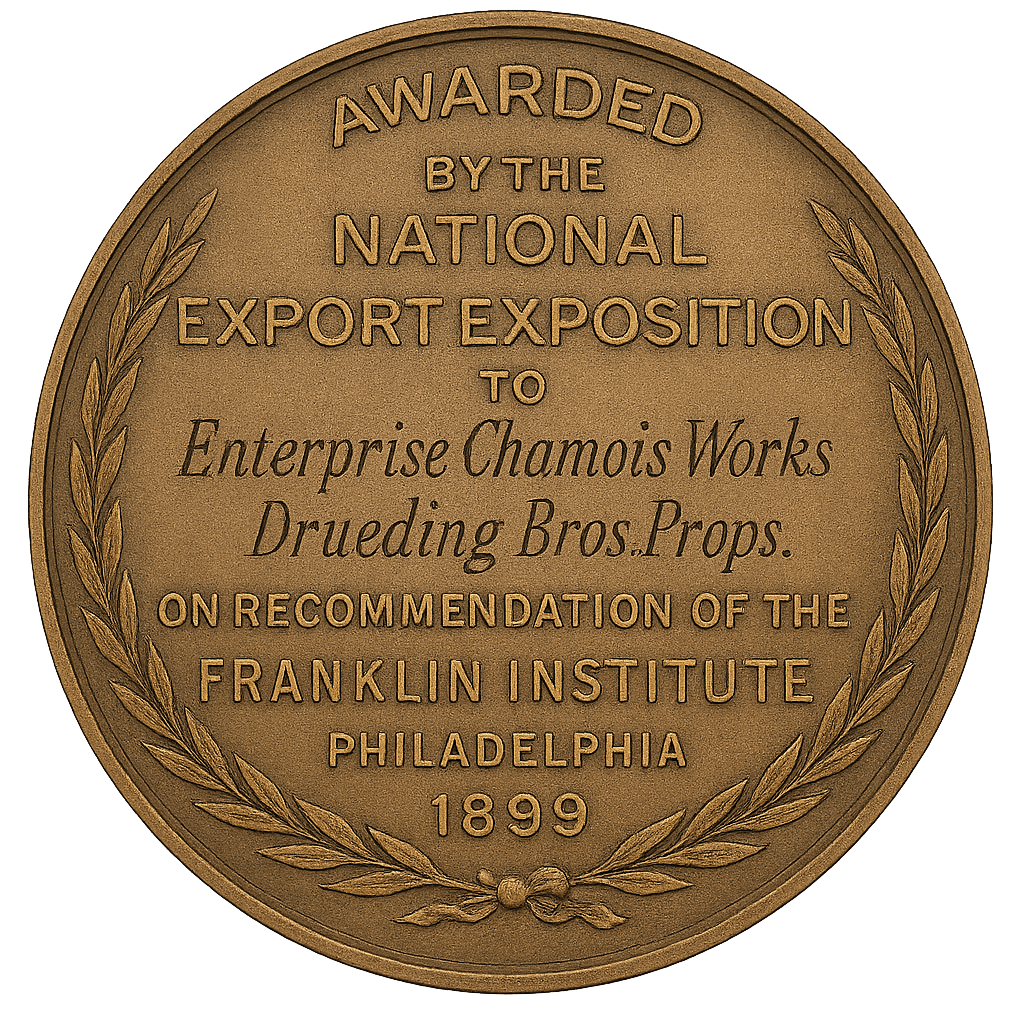

Their process was not perfected overnight; it began in a modest 1,000 square foot shop. Through hard work and persistence, they eventually expanded their operations to 350,000 square feet. In 1889, their product was awarded the National Export Exposition Medal of Meritorious Product by the Franklin Institute.

(E.B. Fortmann – Drueding Bros, 1924)

At its peak, Drueding Brothers Company controlled 70% of the U.S. chamois market (“C. C. Drueding Dies; Leather Executive,” 1939) and became the largest producer in the world, employing over 600 people. (“50 Years of Service at Drueding Infirmary,” 1981)

Skins used in the manufacturing process arrived in 1,000 lb casks, each containing 500 to 600 hides. Chamois manufacturers referred to bundles of 30 pieces as a “kip.” The chamois were cut in various sizes, from 14×23 inches up to 42×36, with popular formats such as 24×36 and 22×34 often labeled as “twenties by thirties.” Depending on size, a kip could sell for $26 to $93. While the full production cycle took about two weeks in Philadelphia, later facilities in North Carolina would use a more extensive three-month process.

(E.B. Fortmann – Drueding Bros, 1924)

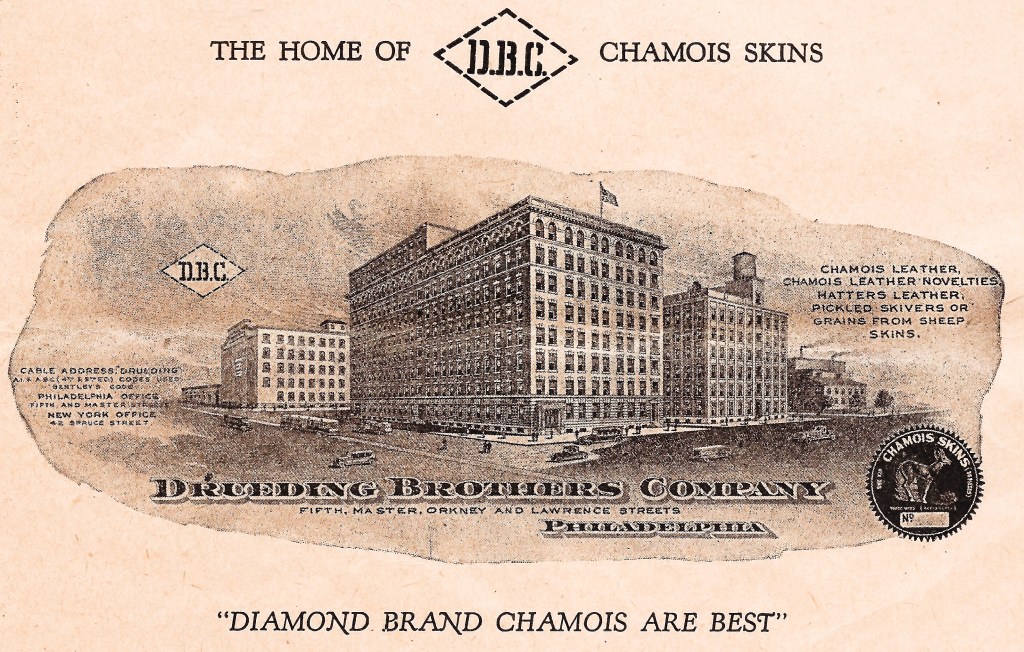

Factories That Shaped the Skyline

The original four-story Drueding factory stood at the northwest corner of Lawrence and Master Streets. (Between N. Orkney and Lawrence) In 1898, it was expanded with a two-story addition. By 1906, the brothers had set their sights even higher, contracting with William Steele & Sons Company to build a grand new six-story factory at Fifth and Master Streets at a cost of $85,000. (“Drueding Brothers Factory Construction,” 1906) (“William Steele & Sons Company Granted Permit for Drueding Brothers Factory,” 1906) That site eventually grew to nine stories by 1920, a monument to the company’s rapid expansion and industrial might.

(Williams, 1921)

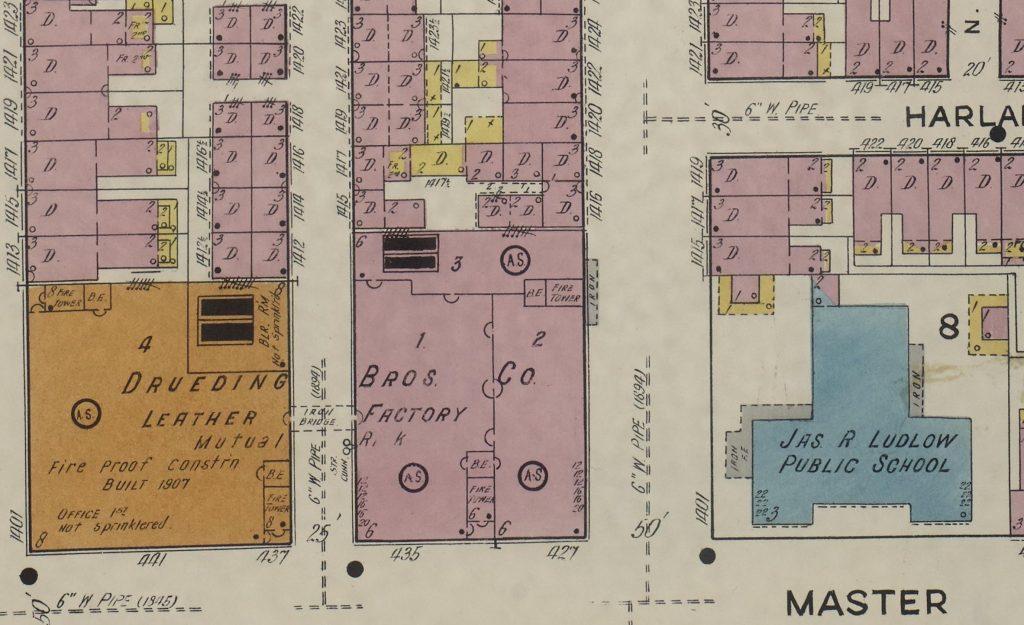

This is photo is a Sanborn Fire Insurance map from 1917 that features both of the Drueding Brothers buildings with an iron bridge between them. Notice the “Jas. R Ludlow Public School” located at the northeast corner of Lawrence and Master St. This will become the future home of the Drueding Infirmary, as described later.

The newer 1907 structure, built in the Classical Revival style, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2012. (“National Register of Historic Places Listings in North Philadelphia,” 2025)

Caring for Workers: The Drueding Infirmary

In 1930, Charles and Henry announced the construction of the Drueding Infirmary, a four-story hospital and retirement home at 413 W. Master Street. They dedicated $1 million (about $19 million in today’s dollars) to the project, with $300,000 for construction and $700,000 for an endowment. Built of limestone and granite, the facility included a 25-bed hospital, senior residences, and even a rooftop promenade with sun parlors.

“These people whom we wish to aid have, through faithful service, helped to make this business the success which it has become in the past fifty years. It is our desire to make a return to them for the work they put into it.”

— Charles Drueding

(“Drueding Infirmary to Be Built,” 1930)

The Infirmary opened on June 27, 1931, and was staffed by the Sisters of the Holy Redeemer, an order from Würzburg, Bavaria. 50 years after it was opened, 3 original nuns were still working at the infirmary and gave an interview to the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1981. They were: Sister Charitona, age 76, Sister Hiltrudis, 81 and Sister Treuhidis, 71.

“I came here right off the boat from Germany” and “I spoke almost no English, but it was such a privilege to be here and everyone was so kind in helping me to learn the language”

-Sister Hiltrudis, Sisters of the Holy Redeemer

“All of us had language problems, but there was so much to be done that we had to learn quickly. I worked in the operating room and it was necessary to know English well”

-Sister Treuhildis, Sisters of the Holy Redeemer

(“50 Years of Service at Drueding Infirmary,” 1981)

A Commitment to Country

The Drueding Brothers were featured in a book called “Munitions Manufacture in the Philadephia Ordinance District” for the work they did in support of World War I.

In support of the war, Drueding Brothers produced:

- 6.5 million hat sweats

- 550,000 steel helmet tube retainers

- 1 million chamois skins

- Thousands of barrels of moellon degras (a tanning agent)

They also donated $1.2 million to the Red Cross and war loan campaigns.

(Williams, 1921)

Community and Culture

Charles was a member of the Union League, Knights of Columbus, and other civic organizations. He also served as a director of Market Street National Bank and lived in the Oak Lane neighborhood at 69th and Lawnton Avenue.

Beyond industry and philanthropy, the Drueding Brothers were woven into Philadelphia’s social fabric.

The company even had a baseball team in the 1920s, making local headlines in 1922 when “Audubon Shuts Out Drueding Brothers” in a 1-0 game.

(“Audubon Shuts out Druding Brothers,” 1922)

End of an Era in Philadelphia

Charles and Henry Drueding both passed away in 1939, marking the end of an era for the company they built.

Henry died first, on May 17, after suffering a heart attack at the Drueding Infirmary. Charles followed on September 27, having received care in that same facility. Both brothers were graduates of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science.

Henry served as a director of the Kensington National Bank and the Industrial Trust Company, and was also a trustee of his alma mater. He held memberships at the Union League, the Whitemarsh Valley Country Club, and the Seaview Golf Club.

By the late 1940s, leadership had passed to Albert J. Drueding, Charles Drueding’s son, who was serving as Vice President of the company.

On January 2, 1958, Drueding Brothers announced it would close its Philadelphia operations and relocate a third of its manufacturing to Goldsboro, North Carolina.

The Goldsboro Chapter

At their new North Carolina facility, Drueding Brothers continued producing chamois at scale—completing up to 6,000 pieces per day.

The chamois-making process was more elaborate than before, taking up to three months and involving cod oil treatments, drying, buffing with large wheels, and finishing. The outer part of the skin, known as “skiver” or “grain,” was used for products like hatbands and book bindings, while the inner portion, the “flesher,” became the chamois. Buffing by-products, known as “fluff,” were even repurposed as fertilizer.

(North Carolina State Ports Authority, 1959)

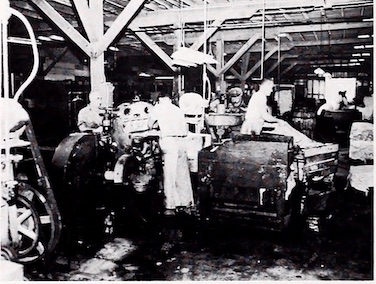

This picture shows “wash out tubs” in the center rear of the photo. The right rear shows “swelling drums”. The left side shows the “stretching out machine”

Their chamois was sold wholesale to drugstores, leather goods manufacturers, automakers, and internationally to companies like Borsalino in Italy, as well as firms in Germany, Australia, and England.

A Tranformation at Drueding Infirmary

In 1954, the Druedings converted the Infirmary to a non-profit nursing home that would continue to be managed by Sisters of the Holy Redeemer. In 1985, the Druedings gave the facility to the Sisters. At that time, research was done to try to understand how the Sisters could provide the most value to community. Bernard “Bernie” J Drueding was involved in the transition. During the mid 80’s drug epidemic, the mission became clear.

Project Rainbow / Drueding Center was opened in January 1987. It opened to support women who had a substance abuse problem and who also had children. Project Rainbow was the first of its kind to support a program that offered a place for women and child to live while the mothers participated in a detox program. The center would provide them with housing and support while they went through detox and searched for a job and permanent housing.

“He is one of the most pleasant, honorable, honest, and ethical men I have ever met. He has a great sense of humor, no self-righteousness or arrogance, and a self-effacing manner. He is just a wonderful, wonderful man who realizes, like I do, that if you are going to get to Heaven, this is one good way to get there.”

-Linda Ann Galante, Center/Project Rainbow’s board chairwoman (2002)

Drueding Center celebrated its 35 anniversary in 2022 and continues to serve some of Philadelphia’s most vulnerable to this day.

(Builderonline.com, 2002)

Carrying On

Albert J. Drueding Jr., the son of Albert J. Drueding and grandson of Charles Drueding, was the last executive of Drueding Brothers and helped oversee the company’s transition to North Carolina.

In 1988, he founded the Drueding Foundation, which became a key supporter of Project Rainbow, a Philadelphia-based service organization.

“Carry on.”

— Albert J. Drueding Jr.

Later Years and Legacy

The original factory at Lawrence and Master was eventually demolished, but the 5th and Master facility still stands. In January 2015, it was sold for $3.9 million with plans to convert it into 172 apartments—offering a new life for a building that once bustled with innovation and craftsmanship.

Meanwhile, the Drueding Infirmary, which evolved into the Drueding Center, continues to serve Philadelphia’s most vulnerable populations.

The legacy of Charles and Henry Drueding lives on—in bricks, in memory, and in the countless lives touched by their generosity and vision.

Bibliography

50 Years of Service at Drueding Infirmary. (1981, June 23). The Philadelphia Inquirer, 5.

Audubon Shuts out Druding Brothers. (1922, September 24). The Philadelphia Inquirer, 23.

Brooding Drueding on the Cusp. (2016, May 23). Hidden City Philadelphia. https://hiddencityphila.org/2016/05/brooding-drueding-on-the-cusp/

Builderonline.com. (2002, March 13). In His Father’s Steps. Builder. https://www.builderonline.com/money/affordability/in-his-fathers-steps_o

C. C. Drueding Dies; Leather Executive. (1939, September 28). The Philadelphia Inquirer, 8.

Drueding Brothers Factory Construction. (1906, October 15). The Philadelphia Inquirer, 11.

Drueding Infirmary to be built. (1930, July 6). The Philadelphia Inquirer, 3.

Drutan Bros. Was First Fruit of Industry Drive. (1967, January 29). Goldsboro News-Argus, 70.

E.B. Fortmann – Drueding Bros. (1924). THE ROMANCE OF A CHAMOIS SKIN – E.B. Fortmann—Drueding Bros. – Philadelphia PA. eBay. https://www.ebay.ie/itm/376360395998

Harry Drueding, Industrialist, Dies. (1945, September 24). The Philadelphia Inquirer, 26.

Home Reared for Aged Employees by Catholic. (1931, July 25). The Tablet, 3.

LEATHER UNIT TO MOVE. (1958, January 3). The New York Times, 28.

National Register of Historic Places listings in North Philadelphia. (2025). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=National_Register_of_Historic_Places_listings_in_North_Philadelphia&oldid=1292643566

North Carolina State Ports Authority (with State Library of North Carolina, G. & H. L.). (1953). North Carolina state ports. Wilmington, N.C. : N.C. State Ports Authority. http://archive.org/details/northcarolinasta1959nort

Obituary—Albert Drueding. (2011, December 14). The Philadelphia Inquirer, B07.

Obituary—Harry C. Drueding. (1945, September 25). The New York Times, 23.

Obituary—Walter F Drueding. (1950, August 13). The New York Times, 76.

Times, S. T. T. N. Y. (1939, May 19). HENRY G. DRUEDING, 82, LEATHER FIRM HEAD. The New York Times, 27.

Times, S. T. T. N. Y. (1951, January 10). CHANGES IN PHILADELPHIA. The New York Times, 54.

T[Mr, Sd. T. T. N., ’ Yok. (1948, October 18). ALBERT J. DRUEDING. The New York Times, 23.

William Steele & Sons Company granted permit for Drueding Brothers factory. (1906, October 24). The Philadelphia Inquirer, 4.

Williams, W. B. (1921). Munitions Manufacture in the Philadelphia Ordnance District. A. Pomerantz & Company, Printers. https://books.google.com/books?id=O_4sAAAAYAAJ